- Home

Page 2

Page 2

Prince of Twilight

Prince of Twilight Oklahoma Christmas Blues

Oklahoma Christmas Blues The Littlest Cowboy

The Littlest Cowboy Edge of Twilight

Edge of Twilight Twilight Phantasies

Twilight Phantasies A Brand of Christmas

A Brand of Christmas Before Blue Twilight

Before Blue Twilight Born in Twilight

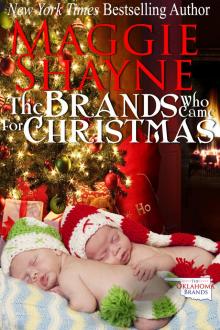

Born in Twilight The Brands Who Came For Christmas

The Brands Who Came For Christmas Twilight Illusions

Twilight Illusions Twilight Memories

Twilight Memories Run from Twilight

Run from Twilight Baby By Christmas (The McIntyre Men Book 5)

Baby By Christmas (The McIntyre Men Book 5) Twilight Fulfilled

Twilight Fulfilled Twilight Vows

Twilight Vows Girl Blue (A Brown and de Luca Novel Book 7)

Girl Blue (A Brown and de Luca Novel Book 7) Beyond Twilight

Beyond Twilight Bloodline

Bloodline Twilight Guardians

Twilight Guardians Blue Twilight

Blue Twilight Twilight Prophecy

Twilight Prophecy Embrace The Twilight

Embrace The Twilight Twilight Hunger

Twilight Hunger Two Hearts

Two Hearts Night Vision

Night Vision Girl Blue

Girl Blue The Rhiannon Chronicles

The Rhiannon Chronicles Oklahoma Sunshine

Oklahoma Sunshine Three Witches and a Zombie

Three Witches and a Zombie Brown and de Luca Collection, Volume 1

Brown and de Luca Collection, Volume 1 The Bliss Book

The Bliss Book THAT MYSTERIOUS TEXAS BRAND MAN

THAT MYSTERIOUS TEXAS BRAND MAN Sleep With The Lights On

Sleep With The Lights On Everything She Does Is Magic

Everything She Does Is Magic Daughter of the Spellcaster

Daughter of the Spellcaster Oklahoma Moonshine (The McIntyre Men #1)

Oklahoma Moonshine (The McIntyre Men #1) Twilight Vendetta

Twilight Vendetta Fairytale

Fairytale Witch Moon

Witch Moon Eternity: Immortal Witches Book 1 (The Immortal Witches)

Eternity: Immortal Witches Book 1 (The Immortal Witches) Dangerous Lover

Dangerous Lover At Twilight

At Twilight Innocent Prey (A Brown and de Luca Novel)

Innocent Prey (A Brown and de Luca Novel) THE OUTLAW BRIDE

THE OUTLAW BRIDE Vacation With a Vampire & Other Immortals

Vacation With a Vampire & Other Immortals Vacation With a Vampire...and Other Immortals

Vacation With a Vampire...and Other Immortals Eternal Love: The Immortal Witch Series

Eternal Love: The Immortal Witch Series Gingerbread Man

Gingerbread Man Zombies! A Love Story

Zombies! A Love Story![Blue Twilight_[11] Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/03/28/blue_twilight_11_preview.jpg) Blue Twilight_[11]

Blue Twilight_[11] The Baddest Virgin in Texas

The Baddest Virgin in Texas Legacy of the Witch

Legacy of the Witch THE HOMECOMING

THE HOMECOMING Lone Star Lonely

Lone Star Lonely Reckless Angel

Reckless Angel Thicker Than Water

Thicker Than Water Born in Twilight: Twilight Vows

Born in Twilight: Twilight Vows Secrets and Lies

Secrets and Lies Million Dollar Marriage

Million Dollar Marriage Fairytale (Fairies of Rush)

Fairytale (Fairies of Rush) Weddings From Hell

Weddings From Hell Love Me to Death

Love Me to Death FOREVER ENCHANTED

FOREVER ENCHANTED Mark of the Witch

Mark of the Witch Shine On Oklahoma

Shine On Oklahoma The Bride Wore A Forty-Four

The Bride Wore A Forty-Four THE BADDEST BRIDE IN TEXAS

THE BADDEST BRIDE IN TEXAS The Incredible Misadventures of Boo and the Boy Blunder

The Incredible Misadventures of Boo and the Boy Blunder A Husband in Time

A Husband in Time Vacation with a Vampire...and Other Immortals: Vampires in ParadiseImmortal (Harlequin Nocturne)

Vacation with a Vampire...and Other Immortals: Vampires in ParadiseImmortal (Harlequin Nocturne) Kiss Me, Kill Me

Kiss Me, Kill Me Wake to Darkness

Wake to Darkness FORGOTTEN VOWS

FORGOTTEN VOWS ANGEL MEETS THE BADMAN

ANGEL MEETS THE BADMAN Oklahoma Starshine

Oklahoma Starshine Colder Than Ice

Colder Than Ice Hollow

Hollow Sweet Vidalia Brand

Sweet Vidalia Brand Who Do You Love?

Who Do You Love? Blood of the Sorceress

Blood of the Sorceress Texas Homecoming

Texas Homecoming Heart Of Darkness

Heart Of Darkness Maggie Shayne - Badland's Bad Boy

Maggie Shayne - Badland's Bad Boy Miranda's Viking

Miranda's Viking Long Gone Lonesome Blues

Long Gone Lonesome Blues Dream of Danger (A Brown and De Luca Novella)

Dream of Danger (A Brown and De Luca Novella) THE HUSBAND SHE COULDN'T REMEMBER

THE HUSBAND SHE COULDN'T REMEMBER Magic by Moonlight

Magic by Moonlight Darker Than Midnight

Darker Than Midnight Forgotten (Shattered Sisters Book 2)

Forgotten (Shattered Sisters Book 2)